Last week I had a lot to say about rhizomes, plant stems that grow not straight up, but across the surface of the earth, or straight down. The rhizome, says electronic musician Aho Ssan, “is the root that stretches out to meet other roots”, in the same way that Aho Ssan collaborates with musicians from other musical genres and perspectives on his 2023 album Rhizomes. He cites the late Martinique poet-philosopher Édouard Glissant, the theorist of créolisation, and we talked quite a bit about Glissant last week too.

That was a lot, last week, so I’ll pause to summarize some important lessons.

Rhizomes matter to the Seventies Soul Dharma, for at least three reasons.

The Lotus Flower — which symbolizes “turning poison into medicine”, according to Buddhist jazzman Herbie Hancock — is among the plants that have a rhizomatous structure. Turning poison into medicine through artistic endeavor, is known, in Buddhist parlance, as boddhisatva work — the work of one who has vowed to liberate all sentient beings.

Aho Ssan’s gloss on Glissant continues: the rhizome is “an underground stem system that fosters connections between various organisms and allows them to flourish collectively.” This is a model of boddhisatva artistry, and is clearly reflected in jazz ensembles. But it’s not only a model for individual artists to cooperate; it is a model for musical scenes and genres and traditions to regard each other, much as linguistic communities regard each other in Glissant’s work. As Hancock put it some years back: “The thing that keeps jazz alive, even if it’s under the radar, is that it is so free and so open to not only lend its influence to other genres, but to borrow and be influenced by other genres. That’s the way it breathes.”

The rhizome is not only a model for musicians and for musical scenes; it’s a map for the listener, for you and me. Each record, in our listening, beckons us to connect to others, and for us to contemplate a set of recordings, a sample of moments, and to see the connections between them as being as meaningful as any components of each record on its own. Thus, Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Be Ever Wonderful” (1977) directs us toward Ted Taylor’s 1963 recording of a different song called “Be Ever Wonderful” , which points us in tune to Taylor’s 1978 re-recording of his song, which is sampled in, and lends backdrop to, Kendrick Lamar’s “DUCKWORTH.” (2017); all of which might propose a detour to Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Love is Life” (1970), with its echoes of the Buddha’s Mettā Sutta, a discourse on loving-kindness. The thought pattern that leads from one record to the next is rhizomatous.

This last point, regarding the mental map of records that you and I can form in our heads, suggests that the Seventies Soul Dharma is a maze of interconnected roots, diving down into the soil, spreading tendrils across the surface of the garden, doubling back, suffering cuts and reconnecting in new ways. Alongside the Seventies Soul Rhizome, conceptually speaking, is a vast record collection, it seems, connected in ways hard to fathom and awaiting new connections. The Seventies Soul Record Collection might look something like this:

…and we are the record librarian, pulling out discs, listening and making connections.

There is a Buddhist story known as Indra’s Net, a metaphor that further helps us students of the Seventies Soul Dharma conceptualize the experience of listening to and dancing to and sharing all these records. Meredith Monk, the intergenre artist who wants to make the voice dance and the body sing (and who talked about creativity as boddhisatva work in last week’s entry), has been working for years on a piece called Indra’s Net, and she describes the concept in these terms:

Indra’s net is a legend in the Hindu-Buddhist tradition. I think that these stories are like teaching stories. They are legends that embody spiritual principles, and this one embodies the principle of impermanence. The story is there was an enlightened king, and I think in the Hindu tradition, he’s a deity. He built a net that covered the whole universe. And within each intersection of the net is an infinitely faceted jewel that reflects all the other jewels. So you really feel that anything that you do affects everything else. And the thing that’s also beautiful about it is I remember my original visualization was that all the jewels are the same, but actually not. Each jewel is unique, and yet we are all connected. So that was very inspiring to me on many levels: spatially, how could I work with this musically, and then just this idea in the world that we’re living in now.

Each of the eight Earth, Wind & Fire songs that we listened to together can thus be thought of as a jewel in this net. There’s a jewel for “Shining Star”, and as we contemplate it, we can see reflected in it all the other elements of the Seventies Soul Dharma. But some, because of their unique shape or their proximity, arrest our attention more assertively: the Manhattans’ “Shining Star”, EWF’s “Saturday Nite”, James Brown’s “Get on the Good Foot”, and so on. You can think of your listening journey as hopping from one record to another in this way. I don’t know if you jump from one jewel to another, in which case your journey looks like the net itself. Or maybe you simply shift your gaze slightly looking at the very first jewel, the “Shining Star” jewel, and move your contemplation to other jewels in their reflected guise; everything can be seen from any jewel, after all. In which case the net, the relationship among the jewels, is spatially collapsed into the initial jewel. And the experience of beauty that you can discern in any jewel draws upon all the other jewels.

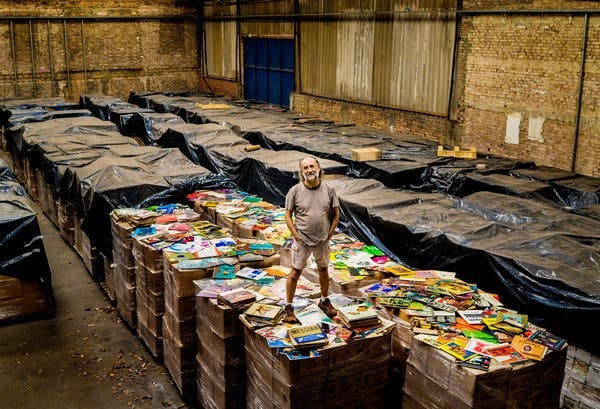

If we think about Indra’s Net in the context of a body of music, a bunch of records, the Seventies Soul Record Collection looks even more forbidding than the wall of vinyl depicted in the photo above. It looks more like the legendary collection of Zero Freitas, the Brazilian bus magnate (that’s the way he’s always described) who aims to acquire every vinyl record ever made. Here he is standing atop some of the records in his collection, which now numbers well into the millions:

There’s something quixotic about this kind of vinylophilic endeavor, and it can be understood in terms of Indra’s Net. Zero Freitas is almost like a character in a Buddhist-Hindu legend. So in love is he (we might speculate) with the reflected beauty in any one jewel/LP that he desires to hold in his hand all the jewels/LPs. If he hears an echo of Doug and Jean Carn’s “Fatherhood” (1973)

while listening to his copy Larry Young’s “If” (1966)

he wants to be able to pull the Carns’ record off the shelf and listen directly. But even a Brazilian bus magnate is unlikely to be able to amass all the records, and even if he does, he might be listening to Larry Young’s record before his eventual acquisition of the Carns’.

Perhaps it’s the quest itself, the pursuit of Zero Freitas’s never-to-be-achieved goal. People of more restricted means than the Brazilian collector derive meaning from crate-digging, searching for records of every type, to isolate beats and harmonies and elements large and small to be used as components of hip hop recordings. The Los Angeles hip hop duo People Under the Stairs — Thes One and the late Double K — composed a beautiful paean to crate-digging, called “The Dig” (2002);

Thes One raps like an archaeologist or a social historian or a gold miner at a neighborhood garage sale:

We got forty crates, black plates, rare grooves, breaks

No 78’s, Vietnam era United States

American funk, private label on major turntables

Sunken treasures that’s in the 4/4 measures

These are not just or even primarily collectibles, though; they are reflections of vast connections in Indra’s Net, connections that Thes One and Double K will multiply when they apply them to the construction of the song we’re listening to, just as producer 9th Wonder did, when he found Ted Taylor’s 1978 version of “Be Ever Wonderful” and layered it into Kendrick Lamar’s “DUCKWORTH.”:

digging worldwide, bringing heritage home

Reconnaissance, innocence, Renaissance elements

Evidence of long lost musical intelligence, big-picture relevance

Double K, meanwhile, bemoans the sacrifices this quest entails:

My fingertips been touching wax since I was a small kid

And ever since I been a big Double, it’s kinda bad

I sit and just listen to all the money that I had

I drop ten on some smoke, you know where the rest goes

For the listener, our experience will always be more like People Under the Stairs’ piecemeal spiritual journey than like Zero Freitas’s ravenous campaign. More important, our quest will always be incomplete: we cannot always, or usually, idenfity all the other jewels we see reflected in the jewel we behold right now.

But we can make the connections; our quest is not to wrap our arms around Indra’s Net, the whole thing, but rather to perfect the spirit of connection-making, Glissant’s poétique de la relation. The narrator of Jean-Jacques Schuhl’s novel Ingrid Caven (winner of the Goncourt Prize in 2000) muses at one point: “J’aime ça, le raccord, la collure, pas les choses : ce qu’il y a entre elles, entre eux, leur rapport. Des idées, des images, le pont entre deux harmonies pour le joueur de jazz ...” [“That’s what I like, the glue, not the things: what’s between them, their relationship. Ideas, images, the bridge between two harmonies for the jazz player.”] The bridge between two harmonies, the Renaissance elements in Vietnam-era American funk. And for that, you don’t need five million albums (though, trust me, sometimes I think that would be cool); it’s enough to listen to the beauty — the inherent beauty and all the reflected elements, identifiable or not — in “Shining Star”.